Inventing Ourselves Through Digital Avatars

The merging of real and virtual worlds asks us to revisit what makes us human and if our humanity exists solely in the physical realm.

Hello everyone!

Thank you so much for reading Zero Percent Sugar. Two weeks ago, we wrapped up our first theme, Taste! Today, I want to introduce you to our theme for the next four essays (two months): Identity!

And let’s get into the essay! 🖤🖋

Animal Crossing: New Horizons, a Nintendo game for the Switch, became a sleeper hit during the pandemic. In the Animal Crossing video game series, players create avatars to manage an island inhabited by animal villagers.

Released during quarantine, many turned to an escapist fantasy reminiscent of our early days online, where we interacted with friends online in virtual chat rooms instead of performing dances on TikTok or taking selfies for Instagram. As of today, Nintendo sold over 40 million copies of ACNH.

Like in ACNH, I spent countless hours on Gaia Online, Poptropica, and the now-defunct TinierMe navigating their digital worlds and making new friends with an online avatar. These avatar-driven social media platforms offered a trapdoor to our everyday lives. We chose our names and selected our physical characteristics, like hair and eye color, outside the constraints of who we were IRL.

During the Internet’s genesis, broadcasting our lives and identities — the same way we do — risked our privacy and safety. Avatars were a great way for people to interact without disclosing their identities. However, I don’t think a technical constraint, like privacy, is the primary draw of avatars. Otherwise, avatar-esque apps today, like Bitmoji, Apple’s Memoji, and Bondee, wouldn’t blow up. Despite the widespread practice of posting every minute of waking life online, what keeps us returning to avatars?

Defining Avatars

The term “avatar” comes from Sanskrit and refers to incarnations of deities on Earth. In 1985, video game developer and technologist Richard Garriott adopted “avatar” to refer to a person’s digital representation in games, which was consequently expanded to online forums and social media.

Applications of “avatar” today are broad. Avatars could be simple profile pictures, or customizable virtual characters we control. I’m more interested in the latter, popularized in platforms like SecondLife, Zwinky, and, Animal Cross: New Horizons.

Fuzzy Boundaries Between Human and Machine

As personal computers became common household items in the 80s and 90s, so did our need to take up space and show up in cyberspace. Avatars allow us to form our identities in these new virtual worlds.

Real and virtual worlds merging prompts us to revisit what makes us human and if our humanity exists solely in the physical realm. In her groundbreaking essay, A Cyborg Manifesto, writer and scientist Donna Haraway presents the cyborg, as “a hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as fiction.”

The cyborg’s emergence reflects society’s move from “an organic, industrial society to a polymorphous information system.” Consequently, boundaries between the physical and the virtual become fuzzy. Think about how we showcase our neighborhood runs on Strava or post about every meal on Instagram. We scatter ourselves across different planes.

All of us are cyborgs. Technology, like vaccines and maintenance meds, augment our lifespans. We rely on state-of-the-art shoe cushions to improve the quality of our walks. We can’t deny how entwined our biology is with tech. Can we say the same for our identities?

Constructing New Selves

Psychographic (my favorite Seth Godin phrase) identity creation is my favorite part about living in the age of mass digital media. The Internet allows us to create new connections and share new experiences with new people — all without leaving the comforts of our rooms. If work-from-home practices aren’t evidence enough, Donna Haraway explores this notion in A Cyborg Manifesto. “The New Industrial Evolution,” Haraway explains, “is producing a new working class, as well as new sexualities and new ethnicities.” Cyberspace is uncharted territory for us to discover and construct our identities, especially through avatars.

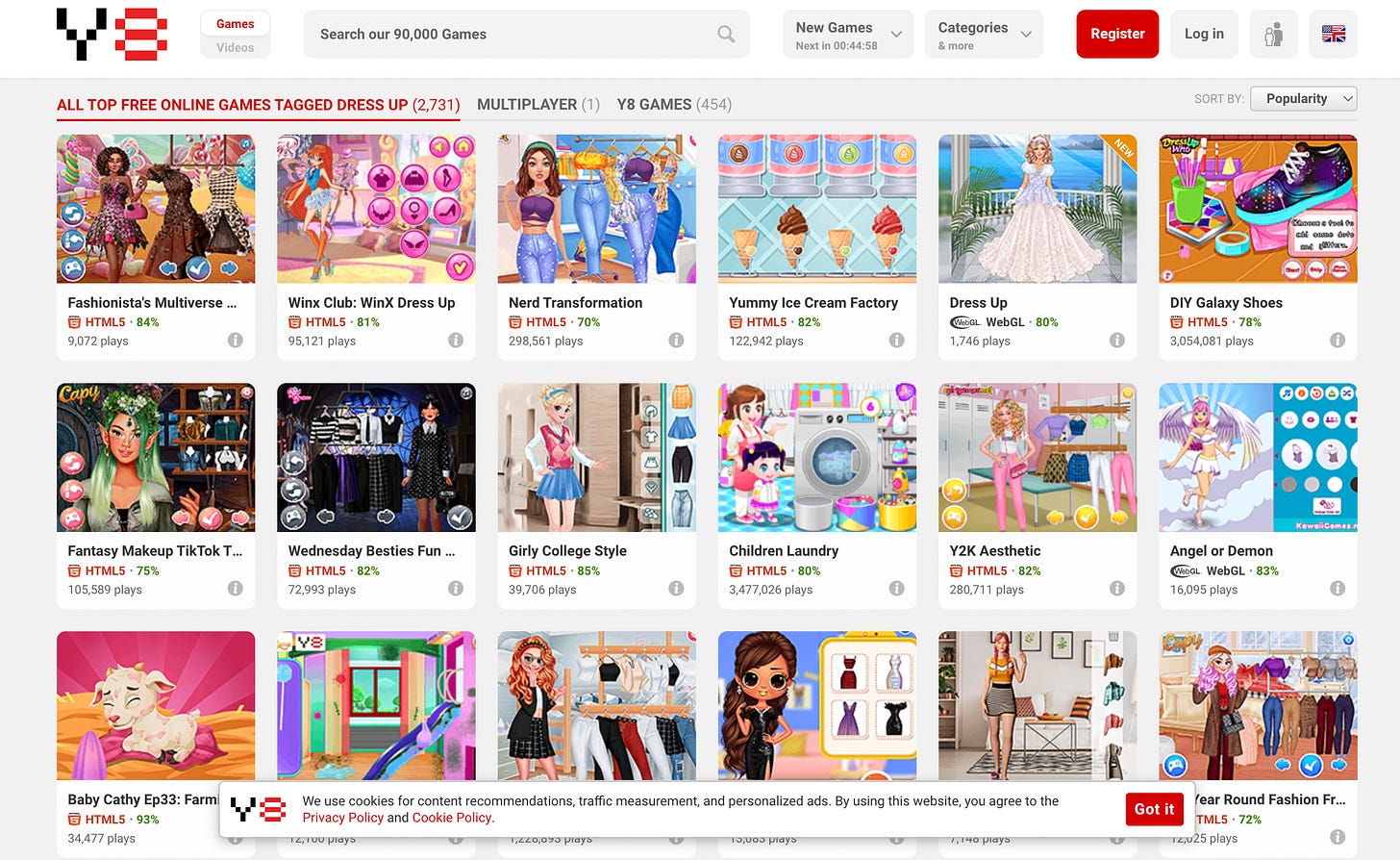

When I booted up the modem for the first time, my eight-year-old self felt like Alice falling through the looking glass. Another world behind the screen was y8.com, a site filled with dress-up and other mini-games.

I spent hours creating iterations of the same perfect girl. Sometimes, she was decked out in chains and spikes, with mascara streaming down her cheeks. Other times, she wore a baby pink gown filled with sequins and pearls. Although my mom refused to give me her email for Zwinky, I had my fill of avatars. Each showed me a different way of taking up space on the World Wide Web.

The limitless possibilities involved in building avatars make it easy for us to project our aspirations on them. In her article, Creating and Regulating Identity in Online Spaces: Girlhood, Social Networking, and Avatars, researcher Connie Morison states that avatar-driven social platforms “promise a space for the cultivation of uniqueness and individuality.” Morrison interviewed a handful of adolescent girls who use their weeworld.com avatars to “project their wishes, dreams, and fantasy lives more than they could with a photograph.” They give us a taste of life if our wishes come true.

Avatars also permit us to live dramatically different lives. Academic Eiko Ikegami conducted ethnographic research on various avatars on SecondLife.com. One case involved a man, Robert, who created a handful of avatars. Each avatar was a playground to exercise empathy and meet new people through the lens of various avatars. Of the experience, Robert said, “I think that I am becoming a better man…”

Fragmenting Who We Are

I cycled through numerous avatars in that dress-up game and my Internet career. My y8.com dress-up avatars introduced me to the practice of taking up different identities online. My ACNH avatar helped me bond with friends during quarantine and just kept me sane. While each avatar personifies my dreams for that season, they introduce a contradictory way of being. I could be infinite versions of myself, although only one at a time.

Using different social media platforms creates a kaleidoscopic self. The Dolly Parton meme says it better than I ever could.

The meme is split into quadrants and each quadrant features a photograph of Parton assigned to a different social media platform. Parton wears an ugly Christmas sweater in the Facebook quadrant, and a teacher’s suit in the LinkedIn one.

Many made their versions of this meme to correspond to their photographs on different platforms, expressing how we curate and perform various facets of our identity. Yet, while diverse, our identities have clear divisions. It’s difficult, and even frowned upon, to show up as our raw and complicated selves.

Limitations imposed by online identity categories reduce our inherent complexity. In her study, Morrison remarks that avatars embody the idealized versions of her participants, yet don’t capture their quirks and nuances. One of the older girls notes, “My avatar doesn’t show that there are other things I love besides music & clothes, such as family & friends & theatre & movies & more.”

Avatars — and by extension, our online personas — splice our personalities to fit into specific contexts online. Simplifying our identities helps us envision goals for ourselves, yet comes at the cost of not celebrating who we are right now.

Avatars offered us a sense of security from online creeps and threats during the 2000’s and continue to provide a place for radical self-actualization. Constructing an avatar, or an abundance of avatars, propels one to both explore and define the type of person one wants to be. However, as we shoot for the stars with our cyber personas, we tend to disregard the beautiful, messy selves of today.

Chaotic Choices

With so many crazy possibilities online, it’s inevitable to aspire to many, often unrelated things. The paradox of choice explains that having a multitude of options hinders, rather than encourages decisive action. It’s why the generation wars stereotypically attribute aimlessness to millennials and Gen Z (“Oh those millennials/Gen Z cannot hold a job etc.”). Or, why we’re always looking for perfection in dating app profiles even before we meet the person IRL.

I could go on and on about these everyday examples of the paradox of choice, yet no one could illustrate it as beautifully as poet Sylvia Plath (born in 1932, clearly not a millennial). In her first and only novel The Bell Jar, Plath likens seeing the identities laid out in front of her protagonist — happy wife, famous novelist, celebrator editor — to picking figs:

“I wanted each and every one of them, but choosing one meant losing all the rest, and, as I sat there, unable to decide, the figs began to wrinkle and go black, and, one by one, they plopped to the ground at my feet.”

Plath speaks of how our aspirations leave us paralyzed. In our quest for more, we find ourselves paralyzed by pondering the roads not taken. I know the fear of seeing a smorgasbord of lives, but not being able to take any of them. However, reaching toward becoming more than our current selves — no matter how scary — reveals our humanity.

We turn to deities to worship and aspire toward, such as those defined by the original meaning of “avatar.” We become cyborgs by augmenting our abilities through technology, like the rudimentary wheel, computers, and medication. Now, we create personal idols in the form of online avatars to let us live all the lives we could not in a single lifetime. The greatest thrills of being human are pushing past our mortal limits and chasing the shadows of the people we dream of becoming.