Finding Comfort In Y2K and Kitsch

Global catastrophe can sway visual culture's direction, yet we still have control over our tastes.

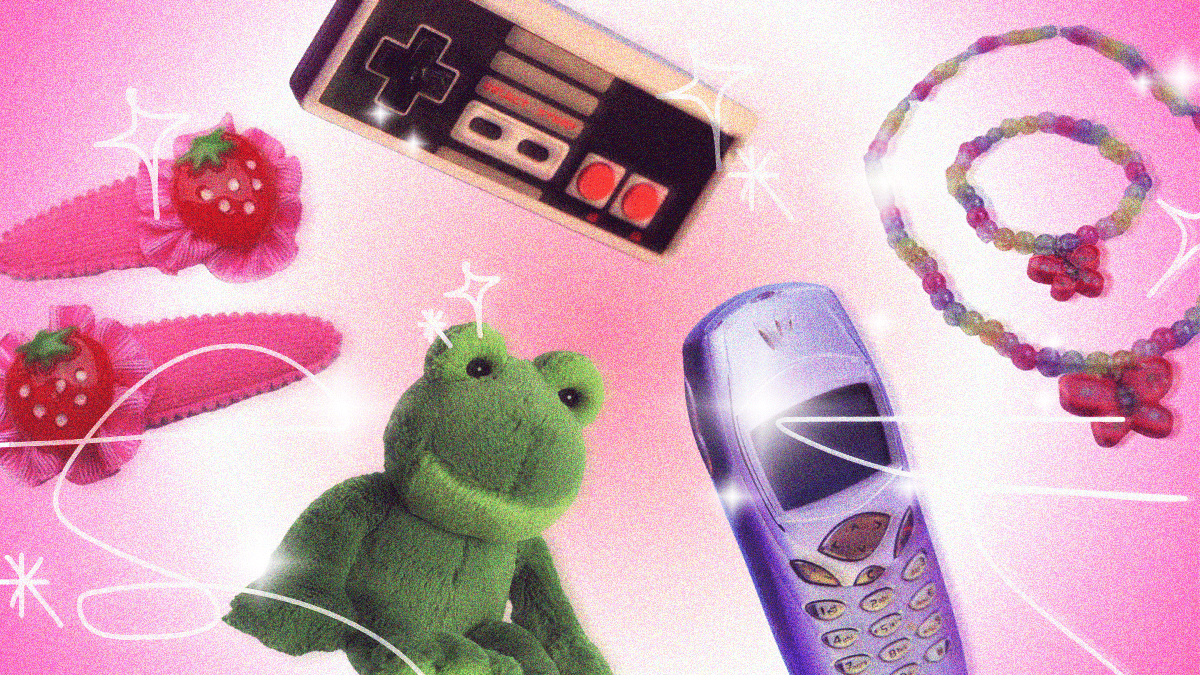

From Lisa Frank puppies on Pinterest to plastic butterfly clips on Instagram, early 2000s style, also known as Y2K, is taking over the Internet. On TikTok alone, videos tagged “Y2K” racked up over 4.8 billion views. In the tech industry, startups such as Polywork base their branding around the visual pillars of Y2K — saturated colors and bold, clunky shapes. And let’s not forget about the pinnacle of the aesthetic’s resurgence in the 2020s: touchscreen phones that flip open. It seems like Y2K is coming back stronger than a 90’s trend — but why?

Some say the reason behind the return of this exaggerated style is the twenty-year trend cycle. Trends tend to come back in style after twenty years, such as 90’s minimalism resurfacing in the 2010s. Alternatively, COVID-induced isolation and hardship compelled the public to turn to fashion and visual culture as a form of escapism. Dopamine dressing, another recent TikTok trend, encourages people to dress the way they want — social norms be damned. And Y2K style, with its bright palette and exaggerated silhouettes, fits squarely into the practice of styling oneself for maximum happiness.

Global catastrophe and the macro-economic climate sway visual culture's direction, yet I’m not convinced that our tastes are outside our control. Former US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright once said, “The difference between humans and other mammals is that we know how to accessorize.” What we choose to adorn ourselves with not only reflects the times but also exposes what makes us human. Yet, people want to look like their favorite childhood cartoon characters or dolls.

Y2K style perfectly encapsulates the simplicity of the past while giving us clear signals on what positive to feel. The aesthetic overwhelms us with uncontroversial visual candy. In short, we love Y2K style because it is kitsch.

Introducing Kitsch

‘Kitsch’ is a loanword from German that refers to mass-produced, garishly cute things that you could find in novelty stores and souvenir shops. Kitsch’s formal characteristics include saturated colors, airbrushing, and exaggerated proportions, which are also evident in the Y2K aesthetic. Some popular kitschy objects today include posters of motivational quotes, garden gnomes, and portraits of anthropomorphized animals playing poker or wearing clothing from the nineteenth century. But, what’s so interesting about kitsch is the intellectual and emotional hold it has on us.

We know kitsch, and by extension, the Y2K aesthetic lacks the subtlety of the high arts. Yet, we can’t help but fill our bedrooms with knick-knacks and bobbleheads of our favorite athletes. What makes kitsch so easy to love?

Art That Spoon Feeds

Kitsch is easy to make and even easier to digest.

The movement emerged during the Industrial Revolution (I touched on this in my previous essay about cultural capital).

Before the Industrial Revolution, only the wealthy and titled could afford to appreciate the arts. They could not only commission extravagant portraits and garments, but they also had the luxury of time to ponder on the meaning of life, while their workers labored in the fields.

Kitsch presents its meaning on a silver platter and makes appreciating art easy and simple.

In the 1800s, countryfolk flocked to the cities for wage jobs in factories. They found more avenues to earn a living beyond just farming for landowners. In business-speak, merchants, tradespeople, and workers attained more purchasing power. With this disposable income, the middle and working classes wanted to decorate their homes and buy things that not only reflected their interests but also elevated their status among their neighbors. The tricky part is that they had more money than before, but not enough to afford the same items as the rich. Enter kitsch.

Kitsch’s on-the-nose approach to art solves the problem of what members of the working class could do with their disposable income. Factories quickly mass-produced kitsch with cheaper materials and labor that could easily scale. This process made it accessible to most people at the time. Its aesthetic gives owners a cultural capital by reflecting their taste, identity, and values. The straightforward approach to art makes it easier for its audience to digest. One didn’t need to spend hours pouring over art history books and looking at a painting to truly understand what a work meant. Kitsch presents its meaning on a silver platter and makes appreciating art easy and simple.

The uncomplicated communication of kitsch reminds me of Y2K. The style of the early aughts is fun and in-your-face. Common Y2K motifs like flowers and smiley faces scream “I AM HAPPY.” While I didn’t get its appeal the first time around, I understand how a “what you is what you get” approach could be refreshing today. We spend so much time on social media deciphering what other people’s lives are like and obsessing over punctuation use (“My dear, Angelica,” or “my dear Angelica” anyone?). We even came up with terms like “ghosting,” “quiet quitting,” and “stealth wealth” to describe how we can say a lot by not saying anything at all. Y2K’s authenticity is a balm to navigating Internet subtext.

Filling The Emotional Void

Another hallmark of kitsch — and Y2K — is its safe and sentimental subject matter. Puppies, doe-eyed children, and mythical creatures often dance around in kitsch work. Contrast these subjects to those found in the high arts: conflict, struggle, and the usual existential crisis. These topics in the high arts make us uncomfortable, compelling us to rethink our perspectives.

Sometimes, we need to sit in dread. Sometimes we just need a visual hug.

Conversely, kitsch aims to do the exact opposite. In his essay On Kitsch and Sentimentality, American philosopher Robert C. Solomon observes, “But the best emotions seem to be the worst emotions where art is concerned, and "better shocking or sour than sweet.” He notes that what prevents kitsch from being taken seriously by art critics and connoisseurs is its focus on positive emotions because we can’t seem to accept nice things. Yet, Solomon sympathizes with sentimentalists: “What underlies these objections, I believe, is a deep but underserved suspicion of emotions, especially those tender emotions that would seem to be most humane.” Kitsch gives us space to lean into these “tender emotions,” that we learned to encase.

With Solomon’s take in mind, it’s no surprise that the Y2K style boomed during a global catastrophe. After looking at COVID-19 infection and mortality rates and the plummeting stock market, we turned to our phones to look at fun TikTok videos as a break. We wanted to go back to a time marked by boundless optimism, which the early 2000s — before 2008 — promised. Designer and creative director Tobias Van Schneider ruminates, “Maybe, just like the early 2000s when this style first emerged, we are feeling optimistic about the future.” Art and design could challenge our worldviews and could also give us much-needed dopamine and oxytocin hits when things get tough. Sometimes, we need to sit in dread. Sometimes we just need a visual hug.

Embracing Kitsch

In 2023, the film Everything Everywhere All At Once won seven Oscars, including the Best Picture award, and smashed many a glass ceiling. What’s so groundbreaking about Everything Everywhere All At Once (well, aside from everything) is how it pays homage to genre movies. The main cast includes action and horror film legends Michelle Yeoh and Jamie Lee Curtis respectively. The plot fuses elements from sci-fi, action, domestic drama, romance, coming-of-age, and comedy while respecting the genre tropes. Everything Everywhere All At Once manages to be subversive on top of being a critical and commercial success by relishing being a genre movie.

Many think of genre films as guilty pleasures, kitschy, and — I hate this term — lowbrow. There’s often that twinge of shame when one says “I love b-rated horror movies,” or “I exclusively watch Christmas-themed rom-coms.” While we can judge genre movies all we want, we can’t deny the amount of joy they bring us. When I was around eighteen, I thought that genre movies were the worst things to be interested in. But, now I really need them to keep calm and carry on.

Like a sunny push against quarantine blues, things that make us feel good — kitsch, Y2K, genre movies, whatever makes you happy — serve a purpose beyond the positive emotions. Art doesn’t always need to reconfigure our realities and induce inner conflicts to enrich our lives. There is value in being in the moment of falling in love and opening ourselves to saccharine emotions that make us cringe. Maybe the secret to getting through life is in the good stuff.

Waymond Wang, the tritagonist of Everything Everywhere All At Once puts it beautifully, “You think because I'm kind that it means I'm naive, and maybe I am. It's strategic and necessary. This is how I fight.”

Additional Sources and References:

On Kitsch, Nostalgia, and Nineties Femininity by Stephanie Brown

Kitsch and Aesthetic Education by John Morreall and Jessica Loy

How 'web kitsch' is helping brands embrace the power of nostalgia by Editor X

Why Do Movies Feel So Different Now? by Thomas Flight

willow by Taylor Swift